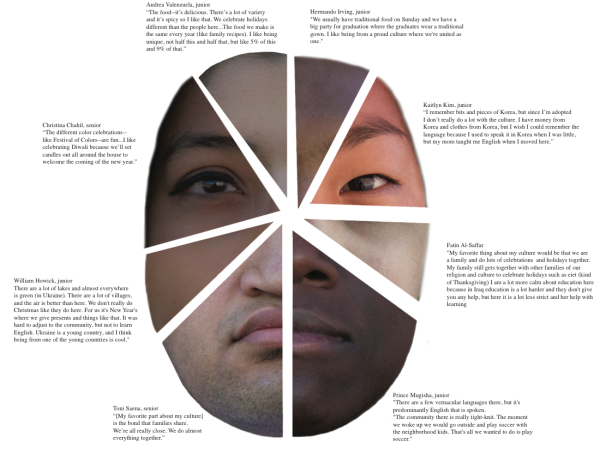

Diversity adds more dimension to student body

Mixed race: sliced into thirds

November 10, 2014

She felt American. As if a person could ever “feel” American. Whatever that means: “American.” All she knew was she felt no different than any other kid her age, and, for senior Jessica Taghvaiee, it would always be that way. But kindergarten began the first of many instances of realization that, despite how similar she felt, people would always categorize her as different.

Taghvaiee recalls being completely confused as the teacher separated the class of six year-olds with white and blonde on one side, and dark-haired on the other. She remembers a lady interviewing her, with questions such as, “Do you speak English or Spanish at your home?” and, “What are the ethnicities of your parents? You speak Spanish at home, don’t you?”

With an Iranian father who left his home country as a teenager seeking a life free of persecution, and a mother who remains rooted to her Mexican culture, Taghvaiee had lived a life that, for the children on the other side of the room and her interviewer, seemed very “different.” But to Jessica, her English-speaking household was as normal as the next.

“You feel like you’re American, but then people don’t treat you as that because you’re different,” said Taghvaiee, “and a lot of people, even people who aren’t American, see an American as someone who’s Caucasian, who just speaks English, eats hamburgers, but I think a lot of us, especially the Caucasian people, are more than that…At school sometimes it’s hard fitting into the different groups…where do I go? Do I go with Mexicans or do I go with Middle Easterners? So it can be hard sometimes, and I sometimes feel left out…because I’m different.”

But she’s not alone. From 2000 to 2010 the number of interethnic/interracial households in the U.S. increased by 28 percent. Since the Supreme Court ruling in 1967, marriages between differing races has become more and more common, increasing the population of multiracial children.

For junior Masami Kanegae, daughter of Caucasian and Japanese parents, her interethnic background influenced her life in small, quiet ways. Although still involved in Japanese culture, Kanegae’s Caucasian ties are often more pronounced, and sometimes preferred. “When I have to choose between the two, I usually just identify as Caucasian because I look more Caucasian,” said Kanegae. “I was taught my entire life to be quiet, reserved, how most Asians are, but I was raised in a society where extroverts are more idolized…[My family] really encourages me to be shy and timid because that’s what’s found attractive in Japan.”

With her mother being pure Tongan and a father whose ancestors range from Irish to Italian, sophomore Mele Morey has seen drastic differences in cultures. “Whenever we get together, we get to see the Polynesians, and they’re very loud and there’s a lot of food,” said Morey. “But when you get together with my dad’s side of the family, it’s very organized…They are a close family, but they are very reserved and they take everything so seriously.”

Morey leans more toward her Tongan side of the family, but admits she sometimes feels out-of-place as only half of either race. “Whenever I’m with my white cousins I feel brown, and whenever I’m with my brown cousins I feel white,” said Morey. “I just be myself in both situations because family will accept you for who you are and who you’re not…[And] I like being mixed. I like the best of both worlds.”

At school, Morey has seen stereotypes surrounding Polynesian culture. “Some people think Polynesians are lazy and that they all have to be about sports,” said Morey, who finds there is more to Polynesian culture than athleticism. “I’m very moved by the things that make the Tongan culture what it is, like the dances and the music and the stories that they tell—my grandma always tells me folktales of Tonga.”

Not all mixed races can be easily noticed. “90% of the time people will guess what I am,” said Austin Clark, senior, “I’ll tell them that I’m half white, they say like Hawaiian or Mexican or Spanish; there’s only a handful of people that have ever guessed Filipino as what I actually am.”

Clark’s mother moved here from the Philippines at the age of 15, unable to speak any English. She didn’t teach her native tongue to her two boys, who only know a few words and phrases. “A lot of people on my mom’s side are full Filipino and there are not many others that are mixed ethnicities like me and my brother,” said Clark, “but we don’t really feel out of place because they really take us in and we’re really family-oriented. The only thing I’d say where we’re out of place is where we can’t speak it fluently like everyone else can.”

Senior George Carrington, on the other hand, always immersed himself in his Mexican culture, including the language. In addition to the advantages of being bilingual and celebrating a wide variety of holidays and festivals, Carrington says there are also disadvantages, such as stereotypes, that influence his life on a daily basis. “Because I’m Mexican, people will judge me because of how Mexicans are, like stereotypes,” said Carrington. “I don’t feel like I’m not a part of it, I just feel like I belong more with Latinos, I get along better with them, I tend to communicate better. I don’t know, honestly. It’s cool that I’m both. I don’t think I prefer to be full of one or the other.”

For Taghvaiee the decision is just as difficult. “I couldn’t choose! They’re all part of me, that’s like cutting myself into three pieces and saying ‘I choose this piece’—I can’t. You kind of feel like you’re pulled here and there and then sometimes you don’t even really feel accepted in any of them, because you may fit in one way, but you don’t fit in other ways…[But] I feel lucky being so diverse because I don’t think many people have the opportunity I’ve had to be in two different cultures and seeing how they’re so similar and learning how people of different areas, different religions and beliefs can be so united in the same things and I just wish people would see that. It’s given me a different perspective than other people to accept everyone and realize that yes we may be different but there’s always that same kind of underlying theme in everyone’s culture.”