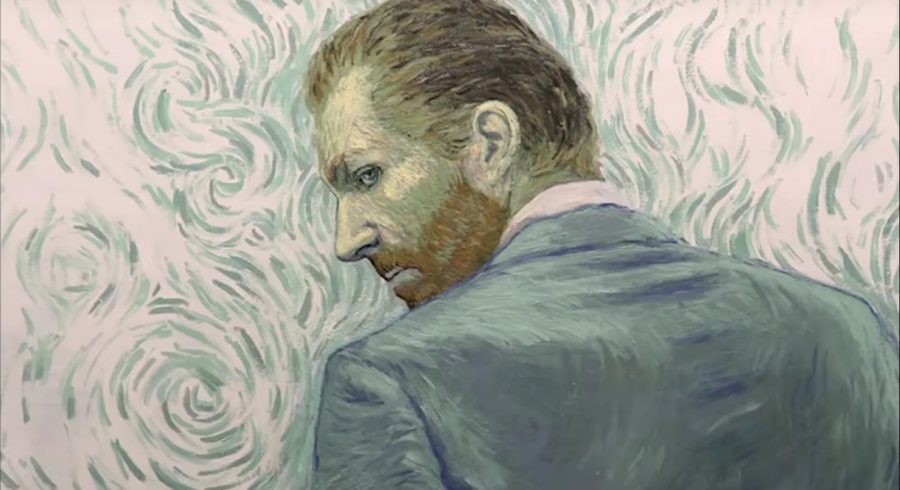

Celebrating the world’s first fully painted movie

December 15, 2017

With over 65,000 frames of oil paintings, done by hand, Loving Vincent has been in the works for over seven years, recruiting scores of artists to recreate the mystery behind the last days of famous artist, Vincent Van Gogh.

Dorota Kobiela, the writer and director of Loving Vincent, did not intend for it to expand to a feature film, but rather an animated short, painting the entirety of it by herself.

“By far the hardest challenge was re-writing the script as an 80 minute film. I see myself as a director, not a writer. I couldn’t just write a biopic like Lust for Life, I could only have scenes that were set in or at least started or finished in Vincent paintings. I would often write scenes that I thought were beautiful and moved the story forward, and then realise they were too removed from the paintings,” said Kobiela.

Kobiela decided to focus on the lives of those who Vincent held close contact with in the last six weeks of his life. Following the story of Armand Roulin, the son of Vincent’s post man before Van Gogh’s demise, a man tasked with delivering the last letter written by Vincent Van Gogh to his brother, Theo. Upon discovering that Theo died only six months after the death of his brother, Roulin becomes intrigued with the last weeks of Vincent’s life, following the shadow of a man who died with so much genius by interviewing those who Vincent painted in those last days including Doctor Gachet, his daughter, Marguerite Gachet, and Adeline Ravoux.

The entirety of this 95-minute movie is shown through animated oil paintings in Van Gogh’s signature style, displaying key characters who appeared in Van Gogh’s works in the last six weeks of his life. And while the story revolves around the last weeks of Vincent’s life, the focus is placed on reliving and understanding moments that shape the life and destiny of humanity.

To recreate the movement and fluidity involved in a live-action film, each canvas was painted and re-painted at least 70 times to compliment the slight scenery changes that would happen in an ordinary movie. Once a single frame was completed on the canvas, artists would take a 6k resolution still and move on to the next frame, using the same canvas.

Perhaps the most intriguing part of this cinematic masterpiece is the artist’s’ ability to recreate Van Gogh’s paintings in a style conducive to film animation.

The most notable Van Gogh paintings amidst the storyline, and in flashbacks of Vincent’s life, were Cafe Terrace at Night, At Eternity’s Gate, Marguerite Gachet at the Piano, and, the title piece, Van Gogh Self-Portrait, each recreated to ensure a smooth transition from canvas to film.

The feat is not necessarily in the storyline, which fell slightly flat, but in one’s ability to recreate Van Gogh’s style and to be inserted into the world which Vincent saw each time he began a new painting; the concept of creating a visually pleasing movie through the application of artistic principles is renowned.

In one of the last letters written to Theo, Vincent perfectly encapsulates what this movie means to artists and humans alike,“We cannot speak other than by our paintings.”