Assisted suicide remains a controversial subject

October 2, 2018

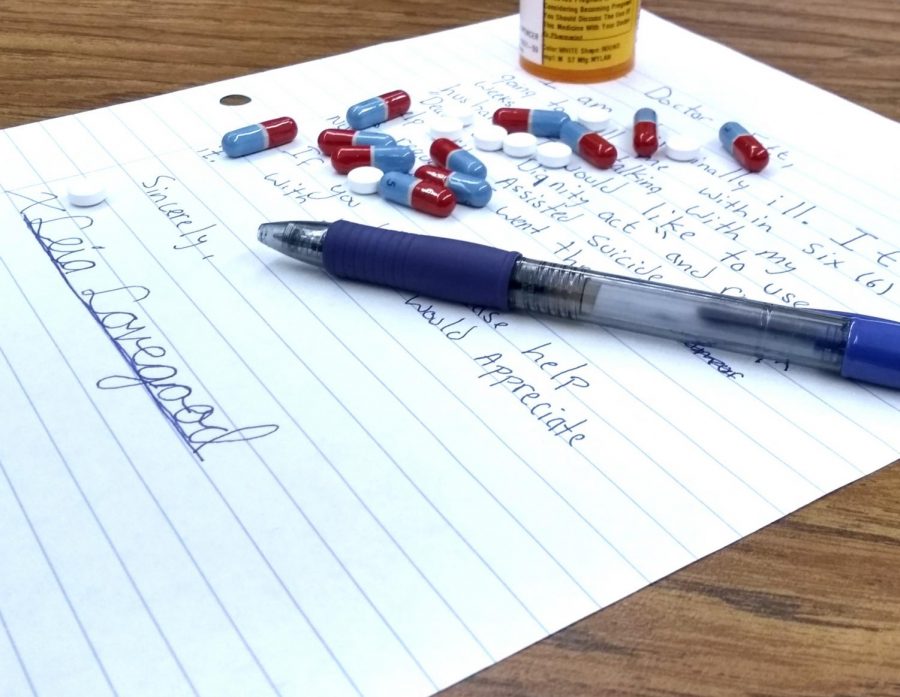

Mandated by law in Oregon, Washington, Vermont, California, Colorado and the District of Columbia, assisted suicide is a physician-administered death delivered to a patient after the patient is diagnosed with a terminal illness and has less than six months to live.

Spurring “Right-to-Die” back in 2014, Brittany Maynard, 29, was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer and moved from her home state of California to Oregon to end her life via doctor-prescribed barbiturates.

Under Oregon’s Death with Dignity laws, first passed in 1997, patients diagnosed with terminal illness are lawfully able to take prescribed life-ending drugs. Following the Maynard Incident, California legislatures ventured into a similar format and created a bill granting that same right to Californians, the End of Life Option Act in 2015.

Despite the slow admittance into the legislature, assisted suicide is still a heavily debated topic within the medical community, with some deeming it to be inhumane and others seeing it as a relief from future pain.

Soo Borson, an expert in Geriatrics and Psychiatry at the University of Washington said, “Most of us have trouble imagining so far in advance what we would have to lose before we, in our present state of mind, would judge our future, deeply demented selves, no longer desirous of living. At the same time, families of very demented patients often tell me: ‘If he only knew how he’s living now, he would never agree to this.’”

Oftentimes, patients with debilitating diseases become too sick after diagnosis to act of sound mind to pursue a course of assisted suicide, which is only available within six months of death. When this occurs, those with living wills or Power of Attorney have the right to decide the future of the diseased individual.

According to assistedsuicide.org, “The degree to which physical pain and psychological distress can be tolerated is different in all humans. Quality of life judgments are private and personal, thus only the sufferer can make relevant decisions. [However], Advance Directives (Living Wills) and Durable Powers of Attorney for Health Care must be respectfully considered by medical professionals at all times.”

Nevertheless, medical professionals still argue the legality and necessity for physician-assisted suicides.

“Our primary role in society is to protect and preserve life while recognizing that our care extends to people who are facing the natural end of life. As a palliative medicine specialist, I know from years of experience that it is possible to alleviate pain and other physical suffering and enable patients to die gently,” said Ira Byock, director of palliative care at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H. “Physicians who remain confused about the difference between killing a patient and allowing a patient to die should not be practicing medicine.”

Under the legal aspects of the laws in qualifying states, as long as the person is of sound mind, terminally ill and has an estimated 6 months of life on this earth, they have the right to a physician-assisted suicide. But these rules don’t apply to patients with dementia or Alzheimer’s, who, after diagnosis, become unable to make such decisions within the arranged time limit.

“There is good reason to think that people… are at greater risk when aid in dying is relegated to the secret and unregulated underground than when it is brought into the open and regulated strictly,” said David Orentlicher, law and medicine professor at Indiana University.